Franz Liszt: Paysage, Number 3 of the 12 Transcendental Etudes, 1826; complicated 1838; simplified 1851.

Listen to the author reading the text

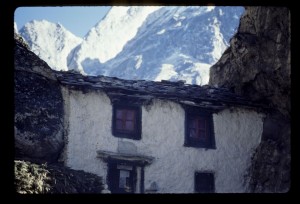

[Like all of the compositions on this album, Paysage is a musical version of an eclogue, or a pastoral poem, an ode to nature, to an unspoiled countryside whose sense of timelessness long ago fell to the Industrial Revolution, which began around the time Liszt wrote this.]

Surrounded by the most fiery and complicated tone poems ever written for the piano, Liszt’s Transcendental Etudes, Paysage is a break from the thunder and tsunami, as is Harmonies du Soir (number 11 of the Etudes, also included here).

Surrounded by the most fiery and complicated tone poems ever written for the piano, Liszt’s Transcendental Etudes, Paysage is a break from the thunder and tsunami, as is Harmonies du Soir (number 11 of the Etudes, also included here).

What is fascinating about the gently undulating countryside of Paysage is that, for all its meditativeness, it is in F, two tones higher than D flat. F is a somewhat brusque and military key, and this is necessary for the turbulence that materializes in the middle of the piece. But, before the view becomes more animated, it sinks deeper into the nooks and dells of the landscape and modulates down into D flat about a minute into the walk, slowing almost to the point of stopping. This is the somnolent effect of D flat. As in the Copland piece performed next, then, the brash metallic key of F falls becalmed into its relative and antithetical opposite key of soothing, drifting, unambitious D flat.

The bucolic day builds to a climax which becomes more and more beautiful and which turns out to be, not surprisingly, in D flat and its close friend, G flat. Exhausted from the revelation of silence in the landscape, the piano falls silent. Single notes fall down like the dusk to the deep bass.

The original accompaniment begins quietly, to be answered by the bells of evening tolling higher and higher, until the bass, with one disquieting distant rumble, fades away to dark. Its flirtation with D flat gave me an excuse to include this exquisite painting of a misty Hungarian vista.

The original accompaniment begins quietly, to be answered by the bells of evening tolling higher and higher, until the bass, with one disquieting distant rumble, fades away to dark. Its flirtation with D flat gave me an excuse to include this exquisite painting of a misty Hungarian vista.

It was only in his last revision of 1851 that Liszt added the title Paysage, perhaps, as Louis Kentner suggests, as part of the process of simplification, or even simplemindedness, although Kentner himself employs similar poetry to discuss pure music. Were there not in Liszt’s mind a transcendental tendency to link literature, vision, and memories of his lost homelands with music, then perhaps it would be wrong for us to succumb to the tinted stereopticons of sight. After all, sight is the great enemy of sound, turning off the ears with the more alluring focus of the eyes. But Liszt, Debussy, Schumann, even the protesting Chopin, knew that everything is part of everything else, as Lévi-Strauss said.