Aaron Copland: Down a Country Lane, Gently flowing, in a pastoral mood, 1962.

Listen to the author reading the text

This is the first piece I ever played from a magazine. To produce this idyll quickly when it was commissioned by Life Magazine, Copland recycled music he had written about refugees trying to integrate and ingratiate themselves into a small Massachusetts town for a wartime film short called The Cummington Story.

Copland adapted the so-called noble theme from the film, a passage imitating the high spirits with which refugees and natives celebrate the harvest at a country fair, a familiar Copland theme, as it must be a theme in all our childhoods, that great brown and orange Charlie Brown pumpkin-patch Thanksgiving, leaves off the trees and smelling of rot around the streets of the town, turning drab alleys into mysterious deep woods by smell alone, the school corridors plastered with scratchy Grandma Moses crayonings of corn and Indians, in retrospect as essential to the American Dream as Copland’s music itself.

Copland adapted the so-called noble theme from the film, a passage imitating the high spirits with which refugees and natives celebrate the harvest at a country fair, a familiar Copland theme, as it must be a theme in all our childhoods, that great brown and orange Charlie Brown pumpkin-patch Thanksgiving, leaves off the trees and smelling of rot around the streets of the town, turning drab alleys into mysterious deep woods by smell alone, the school corridors plastered with scratchy Grandma Moses crayonings of corn and Indians, in retrospect as essential to the American Dream as Copland’s music itself.

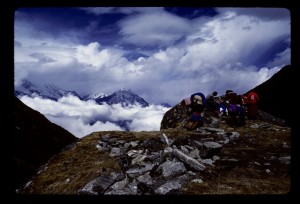

My parents used to subscribe to Life Magazine, as everyone did in those days, as well as Reader’s Digest, hideous bourgeois intrusions into a world otherwise becalmed with the Kadets of America (“Right Shoulder Harms!” with a hollow wooden rifle and a snazzy new khaki uniform), judo (I would stick my hand endlessly into stones filling the wooden box my Grandfather had made me until my fingers became too swollen to fit between the piano keys, at which time I gave up killing, forcing scales rather than assassinations to the forefront of my childhood world and thus eventually creating the same tawdry one-nightstand concert life I would have had had I become an assassin, without the glamor), and Fu Manchu (the devil doctor and his mist-obsessed dacoits who spent most fogbound nights climbing up drainpipes into the brocaded chambers of Sir Dennis Nayland Smith, whose eternal cry was, “Good God, Petrie! It’s Fu Manchu!”—I don’t know why he was surprised, because it was never Jehovah’s Witnesses sliding down the bellrope at midnight), so I can remember being as surprised as Nayland Smith to run across, sandwiched between pictures of war brides and amusing animal postures, two pages that neatly unstapled in the middle, comprising, along with large notes for small eyes, a photo of Aaron Copland and possibly of the country lane in question, although the piece may have just conjured it up in my mind. I am not alone in thinking that this exquisite Bucolic was slyly slipped into a national magazine whose readers had no idea what its calligraphy intimated.

I think back to those eternal, immortal cool summer afternoons under the shade of the now blighted, longsince etiolated oaks, whose stillness you hear at the start of Copland’s calm country afternoon. The progression of the eyes back up to the branch-strewn sky is brought slyly to mind by Copland’s childlike but not childish hints.

The smell of wet wheat and summer dust, the flounce of cottonwoods in the hot breeze slipped out of the glaring cream of the pages, and the clouds bent comfortingly over the darkening magazine as it bent like enfolding trees on the piano stand.

The smell of wet wheat and summer dust, the flounce of cottonwoods in the hot breeze slipped out of the glaring cream of the pages, and the clouds bent comfortingly over the darkening magazine as it bent like enfolding trees on the piano stand.

The dusty backward back road to our haunted hamlet was, I always felt, in F major, like Copland’s piece. The sun would make on the road, when I walked contentedly along it, oblivious to its never-to-be-repeated peace, halos in the haze. Everything was always bathed in dust in the summertime.

I remember the process of kicking a rock, not as the cursory passing incident it becomes in adult life, but as an endless pastime, replete with distinctions of shadow and angle.

Even now as a supposedly wiser and more sensitive version of my earlier self, I find it impossible to retrieve from the Italian sun that chiaroscuro of smoke and sadness among the architectural and personal ruins of Europe that I felt so intensely as a child. We lose with age only the miracles. After a while, I would forget about the crisp sky, the brisk fall afternoon in the skips, limps, feints, and tricks required to pursue the rogue rock, which takes on an anthropomorphic conspiratorial tilt. Trees fold over the road, protecting the suddenly expansive bushes from the desert of the hill high sun. The world turns a deep green, as if it were underwater on a coral reef.

This was the sudden opulence of D flat, hidden inside every otherwise regulation F major day. Then something, a bird, a modulation, a chord, would snap me out of it, back into the crescendo of reality, and the sky was suddenly huge around me, the air filled with hay, with the high meadows dropping off on each side, as if I were at the center of the world, all around me the hay curving off into outer space.

In Mozart’s opera, The Magic Flute, the Prince and his friend must undergo an initiation into the mysteries of life. To me, Copland has similarly wafted us through the afternoon air into the wonders of summer. It may only take three minutes, but when you emerge from this small rain shower of a piece, you’ve transitioned, like the music. Something infinitely sad, beautiful, and bright has happened, and it shines like the hayfield sun, like the reflection of sky in a sprinkler puddle.

Although the piece begins in the key of F, which you will notice is brassier and more determined than the more pensive, expensive, and expansive key of D flat, after a minute the key of D flat is reached. You can hear the air clear and the evening settle in before a crescendo returns the lazy rambler to the initial tempo, key, and day. Copland is very clear about what he wants: “smooth, equal voicing” at the start, then a “slight retard,” followed by a “somewhat broader” area, possibly representing larger fields, then a short D minor interlude played “a trifle faster (but simply),” this being where D flat returns, “gradually slower.”

Although the piece begins in the key of F, which you will notice is brassier and more determined than the more pensive, expensive, and expansive key of D flat, after a minute the key of D flat is reached. You can hear the air clear and the evening settle in before a crescendo returns the lazy rambler to the initial tempo, key, and day. Copland is very clear about what he wants: “smooth, equal voicing” at the start, then a “slight retard,” followed by a “somewhat broader” area, possibly representing larger fields, then a short D minor interlude played “a trifle faster (but simply),” this being where D flat returns, “gradually slower.”

This idea repeats on a larger scale. When the piece shifts sideways into D flat, note the absolute stillness and contentment which transfuse the country road with sun: this is the D flat effect.

Why not a shocking skip into the Emergency Room of heart-thumping modernity? Aaron Copland was too nice for that. He wants to glide into the heart of the land. Thus D flat.